Pieces of electronic music are often accused – and often quite rightly – of being the musical equivalent of Seinfeld. Which is to say, they’re songs about nothing.

EDM circa-2013 kindly slaps ‘uplifting’ vox or “something something PARTY!” samples over the top of its monotony to leave no doubt that it exists in a vacuous vacuum, but what of instrumental tracks? Is there substance slipped between the grooves?

Instrumental music has always resonated with me more strongly than anything lyric-driven – kinda ironic considering I’m a writer, or at least masquerading as one. Sure, I used to memorise lyric sheets as an obsessive teen (who didn’t?), but ask me to sing any album of the past 15 years word-for-word and you’d just get a blank stare.

Sit me down in front of Slash’s guitar solo in Sweet Child O’ Mine or the steamroller jams of Kyuss or the impenetrable musings of King Crimson or Mahavishnu Orchestra, however, and you’ll have not only my undivided attention, but all sorts of crazy theories about what this music has to say for itself.

Instrumentals are universal, unconstrained by language or borders and open to interpretation. In the case of dance music, whatever story the artist is trying to tell is more often than not lost, the obvious response to beats and basslines being a primarily physical one.

And at the end of the day, we all just want punters to shut the fuck up and dance, right? Right.

My old live act D-Ko certainly did, and gave it a good shake across 90-odd shows in Brisbane and surrounds (and occasionally beyond) between ’99 and ’06. Things started to get a (very slow, very steady) roll on for us after we played the Woodford Folk Festival Big Top on the night before NYE 2001/02. We were raw as fuck, leaping between fairly primitive forms of breaks, drum’n’bass and trance (no, really), but we could rock a crowd and we could rock it loudly, if nothing else.

We were camping up there for the week, so our guitarist/occasional percussionist Lilley Rock and his partner Katie booked themselves into a djembe-making workshop, because before bicycle maintenance workshops were an actual thing that’s what people used to do at such gatherings. They got to the workshop to find their names not registered, and walked away djembe-less.

“The drum that never was!” quipped Denno, our other guitarist and resident wild guy.

We all got loved-up on NYE, got blown away by Chi Qui (featuring future Potbelleez frontwoman Blue MC), and ended up where all roads lead at the end of a big night in Woodford – the Chai Tent. The relentless tribal percussion jams that roll out across the straw under that canvas tent are a hippie hater’s hell – particularly when the arrhythmic city folk who’ve just finished a djembe workshop are in there trying to master 4/4 – but on this particular night it was booming.

In the middle of the stage, an African gent from a headline act whose name I can’t recall (it was a decade ago, give me a break) was leading the charge, with drummers on djembes, darrabukkas, congas, bongos, the works spread across chairs, hay bales, you name it. Ben Walsh (The Bird), the god of all live dance music drummers, may have been in there as well. I like to think that he was.

Carrying a drum around when you’re loved-up on NYE is a complete pain in the arse, so I’d instead stuck a pair of drumsticks in my pocket. With no spare skins around to beat on, I took to the back of the stage and started hitting out rhythms on the tent’s thick metal frame – subtly keeping time at first, then starting to fill the spaces with more intricate fills as I found my place in the mix.

Then, the circle leaders dropped the money shot.

“DUN! … Duh-dun-d-DUN! … Duh-dun-d-duh-dun-d-DUN! … … Duh-dun-d-duh-dun-d-duh-dun-d-dun-dun-DUN!”

Around and around it went, the rest of the circle frenetically working the 16ths under it, me with my back to the throng of several hundred dancing around as I was lost in my own clattering rhythms. The cacophony began to quieten down, and soon it was just the leaders playing, and I was unstoppable, tripleting the fuck out of that structure like Stewart Copeland getting all up on a space shuttle thruster in the Walking On The Moon clip.

But I figured this jam was winding up, so pulled away and turned back to the group – only to see the African leader pointing up at me, nodding his head as if to say “yeah brother, you know where the fuck this shit is at”. The rest of the D-Ko crew confirmed it later. I was feeling the love.

It probably wasn’t until March 2003 – a full 15 months later – that I sat down with Lilley Rock at his computer set-up of Cakewalk Pro, Rebirth and whatever version of Fruity Loops was floating around back then to start producing what was as close as I’d come to progressive house at that time.

It had a two-note offbeat bassline, a synth stab taken straight out of the middle of Thee Madkatt Courtship III’s (aka Felix Da Housecat’s) My Fellow Boppers (as featured in Human Traffic, fast-forward to the 2:00 mark for the riff in question) and… not much else.

Until I went into the rehearsal room with Evelyn, Lilley and Denno and started beating out that pattern…

“DUN! … Duh-dun-d-DUN! … Duh-dun-d-duh-dun-d-DUN! … … Duh-dun-d-duh-dun-d-duh-dun-d-dun-dun-DUN!”

The Story Of The Drum That Never Was was a guaranteed live party-starter – not quite Tribal Gathering (with its not so subtle nod to King Of Snake), but always dropped early on to get the dancefloor off its heels. (We were a full band set-up, so it often took a song or two for people to realise they weren’t supposed to just stand there passively and watch like they would an indie band.)

Mid-2004 we decided to embark on an album project, having dropped a fairly rough self-produced EP called 1000 Sunrises at the tail end of ’03. The Mobius Cube team had come into my orbit a couple of years earlier through one of their tracks winning some competition or other, and their sound was immense – like Massive Attack played by Tool fans under a typically utilitarian share house in Newstead, just north of Brisbane’s Fortitude Valley. Now down to just the core production duo of Tane and Luke, it took us one meeting to decide that working with them was a no-brainer.

The process started with me going into their home studio for a week, dropping our programming into Acid Pro, then laying out basic drum patterns for each track – first with the entire kit, then one piece at a time for maximum separation control. The next week I was off into outback Queensland, specifically Winton, to join the art department on the Nick Cave-penned western film The Proposition (which is another story for another time).

Recording continued without me and I returned in December 2004 to a much different sounding batch of songs (which is another story for another time, best told by another group of people). The Story Of The Drum That Never Was, however, had yet to be touched, and wouldn’t begin to take shape until the first half of the following year.

Lilley Rock, the other main tune-writer up that time, departed at the start of ‘05, so it was up to myself, Ev and Denno to try and find some common ground from there.

I don’t know how many hours Tane, Luke and I spent working on that record in the first half of 2005, but it was somewhere in the vicinity of a metric fuck-ton. Our approach to a day’s work was simple, effective, occasionally counterproductive and quite possibly insane.

We’d convene at Newstead around midday, then walk down to the Waterloo Hotel where I’d sling a carton of Hollandia beer (being the cheapest and easiest to drink) over my shoulder and walk back to theirs to put them in their VB can-shaped cooler. With the first beer cracked, we’d bomb a dexie each – dexies being Dexedrine, the ADHD and Narcolepsy medication that also functions as the cleanest, most focus-enhancing speed you’ll ever take – then crush another up on a plate to snorkel between us.

Then we’d get to work.

Enough ideas were generated in those sessions to power several dozen albums, many of them terrible, but there was some serious inspiration flow going down. Ev, Denno and the Mobius team’s housemate B-Funk (who subsequently became our bassist) would pop in every couple of days to add their parts to tracks that constantly evolved. In fact, they were evolving so rapidly that I’d often turn up the day after a particularly feverish night-time session to discover Luke had nuked half the parts before anyone else had a chance to review them, sending them off to what we dubbed ‘the vortex’.

Being one of two purely instrumental club tracks on the record (the rest having moved towards more traditional song structures, driven very much by Ev’s vocals), The Story Of The Drum That Never Was was one of my babies. It was also barely a sketch, so we had to get to work.

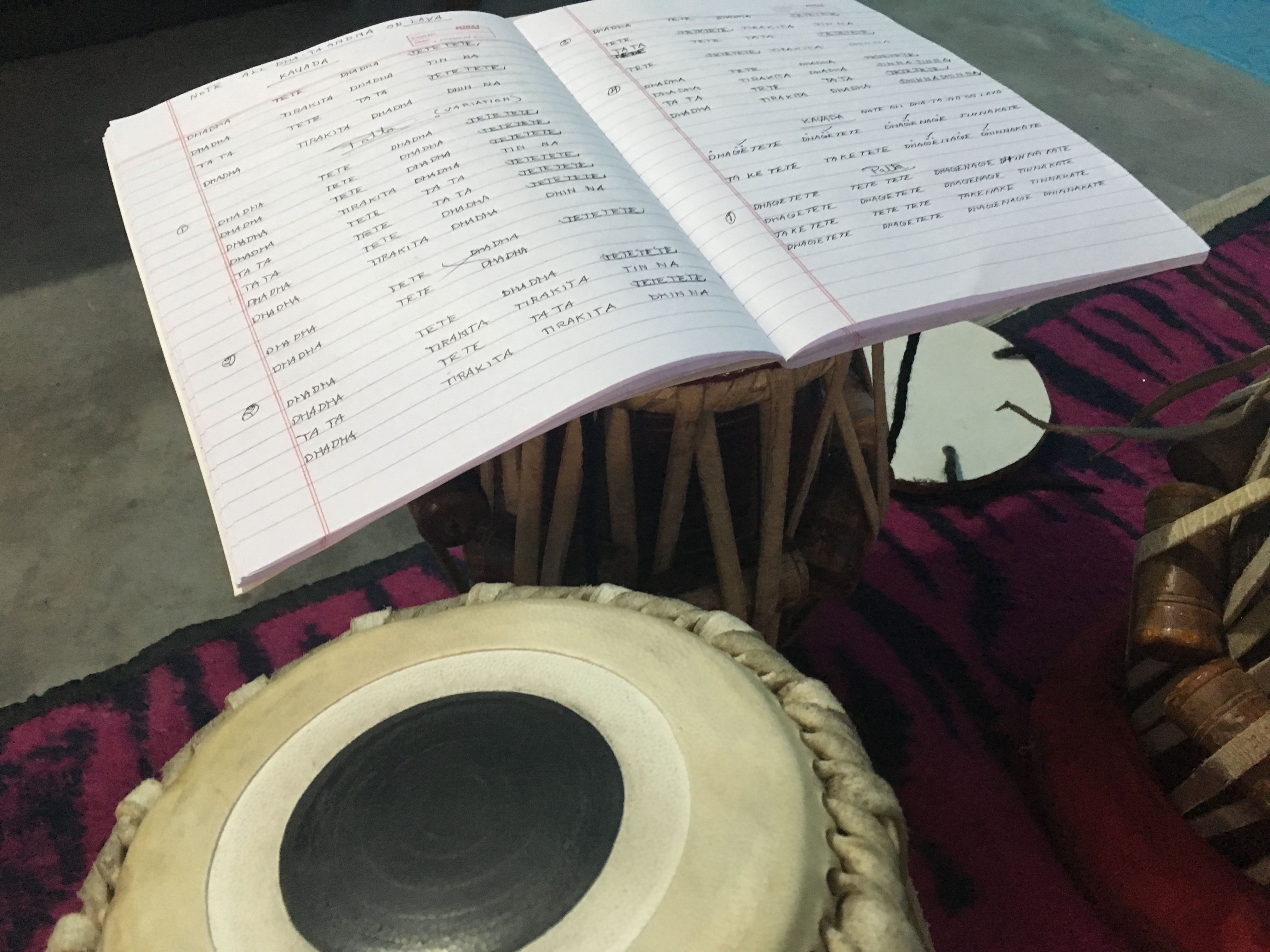

My vision was for the drums to pound as selfishly as those in [Love] Tattoo’s Drop Some Drums, an effect we never quite achieved. The percussion outside the central drum kit (all played live, with one shots of hi-hats and cymbals sampled and laid out around kick/snare) is a combination of toms and old rusted paint and kerosene tins, which we collected from the back of a nearby factory for me to beat out the drum hook until they were quite literally shattered.

By this stage we were starting to think about how we were going to recreate these dense new tracks live. I spotted a Yamaha RS7000 – an all-in-one synth/sequencer/sampler from those halcyon days of the humble ‘groovebox’ – going for $795 at local retailer Musiclab, and bought it that very day. From memory we pulled it straight out of the box and got to work on Drum, laying out the bassline, some more synth stabs, pedal notes, a crazily effected breakdown swirl and swoosh, and the various arpeggiated lines you hear bubbling away throughout the song.

Still, something was missing. At some stage in proceedings, one of Ev/Denno/B-Funk had brought the lilting refrain that tops and tails the track to the party, but we were still missing our hook.

Then it happened. Denno rocked into the studio one sunny afternoon as Tane was messing around with an early demo of Native Instruments’ Guitar Rig effects processor. Within minutes, we’d found the sound – a preset effect that cut the guitar up to sound like an arp, with distortion and delay and all the other signatures of the Denno sound.

He jammed a two-note hammer-on riff along with half the song, it worked instantly, and we hit record. What you hear on the track is a first take, completely unrehearsed, and the icing on the cake.

The track had finally found its epic scope and the story the music told had become perfectly clear to me. This wasn’t just about a phantom drum workshop – it was about a group of horseback riders in a vast desert, brought together by a shared vision to embark on a quest that may not have an end.

We set up a microphone so I could add the finishing touches, including some crazed rantings (think Tool’s Disgustipated) that were eventually whittled down to a detuned version of the below…

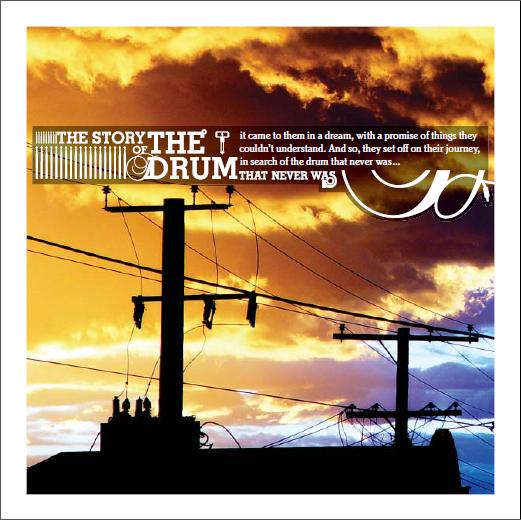

“It came to them in a dream,

With the promise of things they couldn’t understand.

And so, they set off on their journey,

In search, of The Drum That Never Was.”

With some final cut and polish from Tane and Luke (who returned after splitting midway through the recording process – they were those kind of sessions) the track was done and the album pressed in November 2005, nearly four years after that fateful night in Woodford.

So the next time someone tells you that dance music is about nothing, feel free to point them in the direction of the story of The Story Of The Drum That Never Was. As far as songs about nothing goes, it’s almost as deep as an episode of Seinfeld.

CREDITS

D-Ko – The Story Of The Drum That Never Was

Taken from the album The Rule Of Thirds, © Copyright D-Ko 2005.

Written by D-Ko

Arranged, produced & mastered by Tane Matheson & Luke O’Sullivan

Recorded at Mobius Cube Studios, Brisbane, Australia

Art Direction by Gary Loo Bun

D-Ko was …

Simon Dennes: Guitar, FX

Evelyn Golding: Lyrics, Vocals, Synths

Kris Swales: Drums, Percussion, Synths, Vocals, Backing Vocals

Ben Retschlag: Bass