I don’t remember much about my brief stint delivering pizzas for Eagle Boys’ Toowoomba CBD franchise in the winter of 1996, but I do remember this: the franchisee was the brother of Canberra Raiders cult figure Jason Death, and my car stereo was mostly pumping out a sitar and tabla recital on a cassette that may have been bequeathed on me by a cherished school friend who’d recently returned from a pilgrimage to the Indian subcontinent.

The sitar guy was cool and all, but what really stood out was a tabla solo which started languidly enough before exploding into an onslaught of “giggidy-giggidy tah” vocal percussion and warp-speed dancing of fingers across goat skin so frenetic Dave Lombardo would be blushing from behind his own formidable battle station.

I was going to learn this instrument one day, really I was; just like I was going to emulate Jackie Chan’s wackiest moves from The Young Master after taking kung fu lessons; just like I was going to play the Big Day Out (hang on, that did happen).

But despite a brief phase of writing Tea Party-inspired, eastern-tinged space rock, and seeing Bobby Singh saddle up beside The Bird so many times that we eventually started a band just like them which sounded completely different, life went on and the moment passed.

When I came to India for the first time in 2013, classical music was the furthest thing from my mind – I was here to watch (Australia lose) cricket. Two weeks in Delhi/Goa soon extended to a month of criss-crossing the country in planes, trains and automobiles (but mostly trains), and the home stretch deposited me in Varanasi for a touch over 24 hours to get snaked by touts, watch over-commercialised religious ceremonies and definitely not immerse myself in the Ganga.

Somewhere amidst the twisted and tangled laneways, a music store beckoned me inside. More hole-in-the-wall storage area than retail showroom, it nonetheless had enough floor space for one proprietor and one slightly bronzed videshi to seat ourselves and put a pair of sitars through their paces – remembering the odd riff from that brief-yet-intense Tea Party phase proved the ultimate ice breaker.

It was agreed I’d return for a one-hour tabla lesson the following morning, which I did… and I sucked.

Every bad habit from 23 years of drum kit/djembe playing still resided deep in my hands, wrists, shoulders and back – too tense, too sloppy, too slumped – and we frustrated each other through 60 minutes of basic theory before exchanging contact details so I could share the photo I’d taken of our brief time together.

Secret tabla players’ business.

“If you come back and study with me for one month, you’ll be able to play tabla by the time you leave,” he assured me.

That free month finally arrived when I walked away from a 28-month sprint on the corporate hamster wheel to use some of my time in India for exactly what I’d intended it for when I relocated permanently to Delhi in January 2016 – living in India.

As luck would have it, my man in Varanasi dropped off the grid at precisely the time I was ready to escape Delhi at its summery worst, but Doctor Google eventually led me to the hills of Dharamshala for a month of intensive training with another tabla guru whose 45-plus years behind the skins started as an eight-year-old.

*****

Upper Bhagsu is a sleepy little hamlet nestled among the pine trees of the foothills of the Himalayas, just around the mountain from the Dalai Lama’s monastery in McLeod Ganj, just up the logic-defying windy roads from Dharamshala, home of a contender for the world’s most picturesque cricket ground (where, yes, I have also seen Australia lose to India).

Yep.

Bhagsu must’ve been quite something when the hippie trail was in its infancy, and it still exudes a certain charm provided crumbling concrete pathways, guesthouses which seem to have erupted out of the ground, and the modern trappings of an ‘alternative’ lifestyle (yoga training, massage courses, coffee shops mandated to play Hotel California at least once daily) are your cup of chai.

Indian travellers from Himachal Pradesh’s neighbouring state of Punjab tend to bypass Upper Bhagsu on their way to the nearby waterfall, so the steep incline’s population comprises a mix of Indian shop keeps (many escaping the heat of Varanasi), tourists (most escaping the heat of Israel), and donkeys ferrying building supplies to the next generation of guesthouses rising from the cement ruins.

I greet my guru ji, Rohit Mishra, on the Sunday afternoon before my four weeks of intensive training begins. He’s had me accommodated above the Cosy Corner restaurant, a little further up the hill from his transplanted Varanasi Music Centre (which here is a couple of modest rooms for he, his wife Anita and nephew Mani to teach tabla, singing and harmonium among other things).

My room is spartan and not entirely immune to the first sprinklings of the monsoon when it pours in at a 45-degree angle, but the nondescript restaurant’s thali has such solid word-of-mouth that visitors brave the extra hundred metres of hill just to sample it.

So there I was. Alone, not entirely sure my mostly retired drummer’s heart was in it, and a long way from turning back.

*****

If playing rock on the drum kit or rolling tribal rhythms on a djembe is like learning your times table and playing drum’n’bass or unleashing thrash-metal double-kick fury is doing long division in your head, sitting behind the tabla is like encountering the quadratic equation for the first time. Impenetrable at first, slowly the elements begin to make sense in isolation, until you finally solve it and it all makes sense.

Except unlocking that first puzzle only reveals another one, and another, and then you realise there is no ending. You just roll on and on and on into the distance, on a quest to solve Pi to the final decimal place.

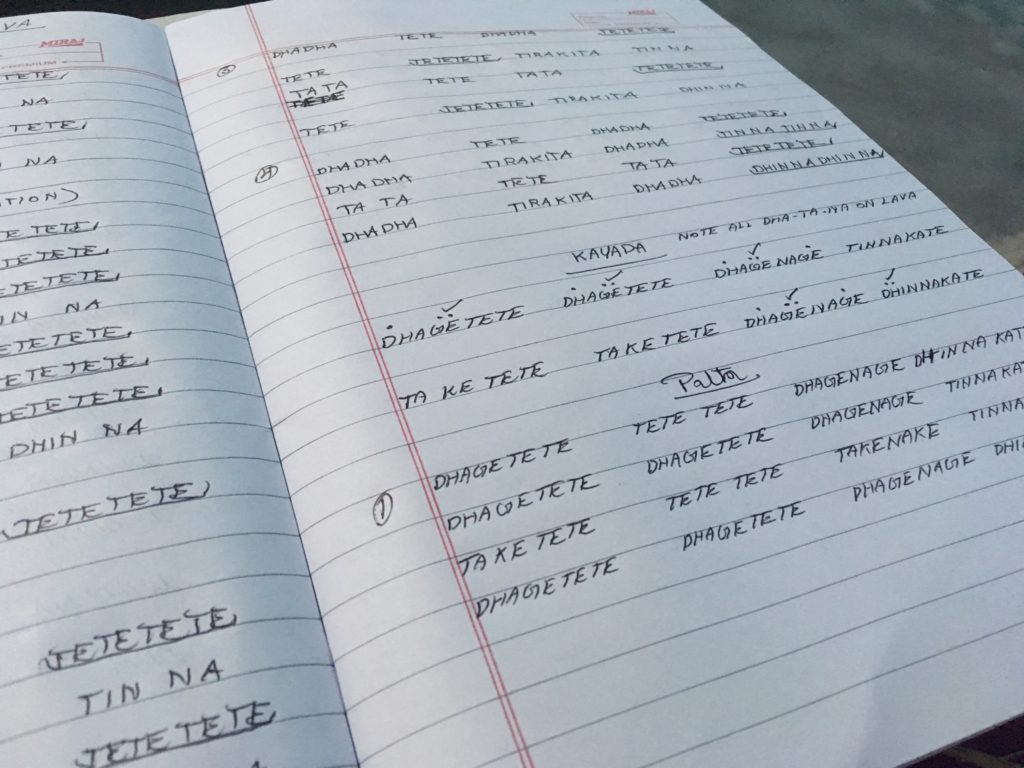

There are essentially around 10 basic sounds (ge, tin, te, ta, et al), then as many again (dha, dhin, tirakita, and tete, in which each ‘te’ is played with different fingers) formed from combining the aforementioned sounds played on the bayan (the bassy one) and the tabla (the trebly one). Like the English language, different notations can sound the same in practice – so while ‘Ti-ra-ki-ta-ta-ka’ looks like you’re playing five different sounds (with the ‘ta’ the only one played twice), the ‘Ti-ra-ki’ and ‘ta-ta-ka’ sections are actually the same pattern repeated.

Confused yet?

Okay, let’s instead pretend that the sounds are notated as su-per-cal-i-frag-i-lis-tic-ex-pi-al-i-do/tro-cious.

Using this equally insane notation, a kayada (or basic pattern) would read a little something like this.

Su-per-cal-i | frag-i-lis-tic | ex-pi-al-i | do-cious

Su-per-cal-i | frag-i-lis-tic | ex-pi-al-i | tro-cious

Then the first palta (variation) might look like this.

Su-per-cal-i | frag-i-su-per | su-per-cal-i | frag-i-su-per

Su-per-cal-i | frag-i-lis-tic | ex-pi-al-i | do-cious

Su-per-cal-i | frag-i-su-per | su-per-cal-i | frag-i-su-per

Su-per-cal-i | frag-i-lis-tic | ex-pi-al-i | tro-cious

Then the eighth (!) palta might kick things up a notch, going…

Ex-pi-ex-pi | ex-pi-super-super | ex-pi-super-super | fragi-cali-super-cali

Su-per-cal-i | frag-i-lis-tic | ex-pi-al-i | do-cious

Ex-pi-ex-pi | ex-pi-super-super | ex-pi-super-super | fragi-cali-super-cali

Su-per-cal-i | frag-i-lis-tic | ex-pi-al-i | tro-cious

Then there’s the tehai, a grand finale which calls back to the kayada but flips the phase on timing and doubles down on dramatic flourishes…

Su-per-cal-i | frag-i-lis-tic | ex-pi-al-i | do-cious

su-_-_-_ | Ex-pi-al-i | do-cious | su-_-_-_

Ex-pi-al-i | do-cious | Su_-_-_ | _-_-_-_

Su-per-cal-i | frag-i-lis-tic | ex-pi-al-i | do-cious

Su!

Then imagine the above, where ‘su-per-cal’ and ‘ex-pi-al’ are sometimes the same and sometimes different, all ultimately played at three times the speed Mary Poppins ever bothered to in a number of possible combinations so lengthy the grand masters have been known to not repeat themselves during recitals stretching across several hours, and you end up with one mostly retired tub-thumper, lying semi-catatonic in a dark room as rain tumbles down on his first day off the tools in a week, getting pummelled by Poppins-on-trucker-speed as Guru Ji’s nephew practices at full pace in the adjacent quarters, wondering if it was too late to climb out of the rabbithole.

There’s a reason I’m a mostly retired drummer, even though I could happily play gigs until my body is incapable of doing so any longer. That fleeting moment of eye contact with a punter on the floor when you just know this hour of the night is making their week (and yours), the rush when you build slowly out of an epic breakdown then nail some ridiculously intricate fill across four drums and three cymbals and the energy of the dancefloor suddenly kicks up another notch despite already having heaved itself stupid for the past 47 minutes?

That’s the easy part.

But you’ve gotta have the hunger. Jamming, practicing, getting gig-fit – if the hunger’s not there, you don’t get the hour of glory. Muscle memory might be enough for you to fake your way through, but deep down inside you’ll know you’re well off the pace.

In that dark cement room with Guru Ji in Bhagsu, in my modest digs a couple of hundred metres up a 45-degree hill, there is no muscle memory to fall back on. There is only me, 25,000 rupees worth of percussion instrument, and a covers band somewhere across the hillside whose mistake-riddled repertoire consists of a variety of Red Hot Chili Peppers odes to California and Hotel California itself, played incorrectly night after night.

Every day is an emotional rollercoaster, which seems to spend the majority of its time stuck upside down on its most perilous loop. Whenever my wife Rakhi asked how each class went, answers ranged from “awful” to “decent” to “rubbish” to “pretty good actually” to “shithouse”, but those answers could be applied on a macro level to each stroke of each drum, or the kayada/palta/tehai combo that were ‘perfected’ on Day 4 but borderline unplayable on Day 11.

As for that sliding bass note, the tabla’s most distinctive sound?

The penny finally dropped on Day 17, though continues to slip through my fingers (and more importantly, the heel of my hand) from day-to-day, bar-to-bloody-bar. Meanwhile, Guru Ji effortlessly makes the bayan sing, the bass tone more than just a sound but a three-dimensional, shapeshifting entity that can be as playful or destructive as its mood takes it. Just getting ‘dha-dha’ (two different sounds, for those playing at home) to sound the same twice in a row feels like a small victory, but it’s impossible to shake the feeling you’re operating in 3.14 when there’s someone several-hundred decimal places deep right beside you.

*****

It was the night of Day 21 when the full weight of the Tabla Paradox began to take hold: You need to play to get better, but sometimes playing only makes you feel worse. For someone whose skills had outstripped his Year 8 music teacher within minutes of sitting behind a drum kit for the first time, this was a harsh reality check. What do you do when the skills you need aren’t already lying dormant within? How hard do I have to work for this? Maybe I’m just no good?

After thrashing away frustratedly, like that angry Year 8 kid once tried to emulate Lombardo, for 45 minutes before going to bed that night, a restless night/morning of soul searching was quickly soothed by Guru Ji.

“When I first started to play tabla, it used to make me depressed,” he assured me. “Please don’t stop, Kris ji. Your sound is fine – you’re just confused.”

I’ve been back home in Delhi three weeks now, stealing an hour here and there to keep practicing in between the rigours of a daily exercise routine, taking a half-decent stab at cooking Indian food, and trying to infiltrate the Indian sports media industry.

My technique is still sloppy, my left hand still too ‘closed’ when I ramp up the bass pace, but some days I climb off the floor feeling like I’ve actually had some fun.

To borrow shamelessly from my favourite rating system for bad films, what was shaping up as a fiasco finished a long way from a flop.

With another 40 years of practice, it may even end up a secret success.

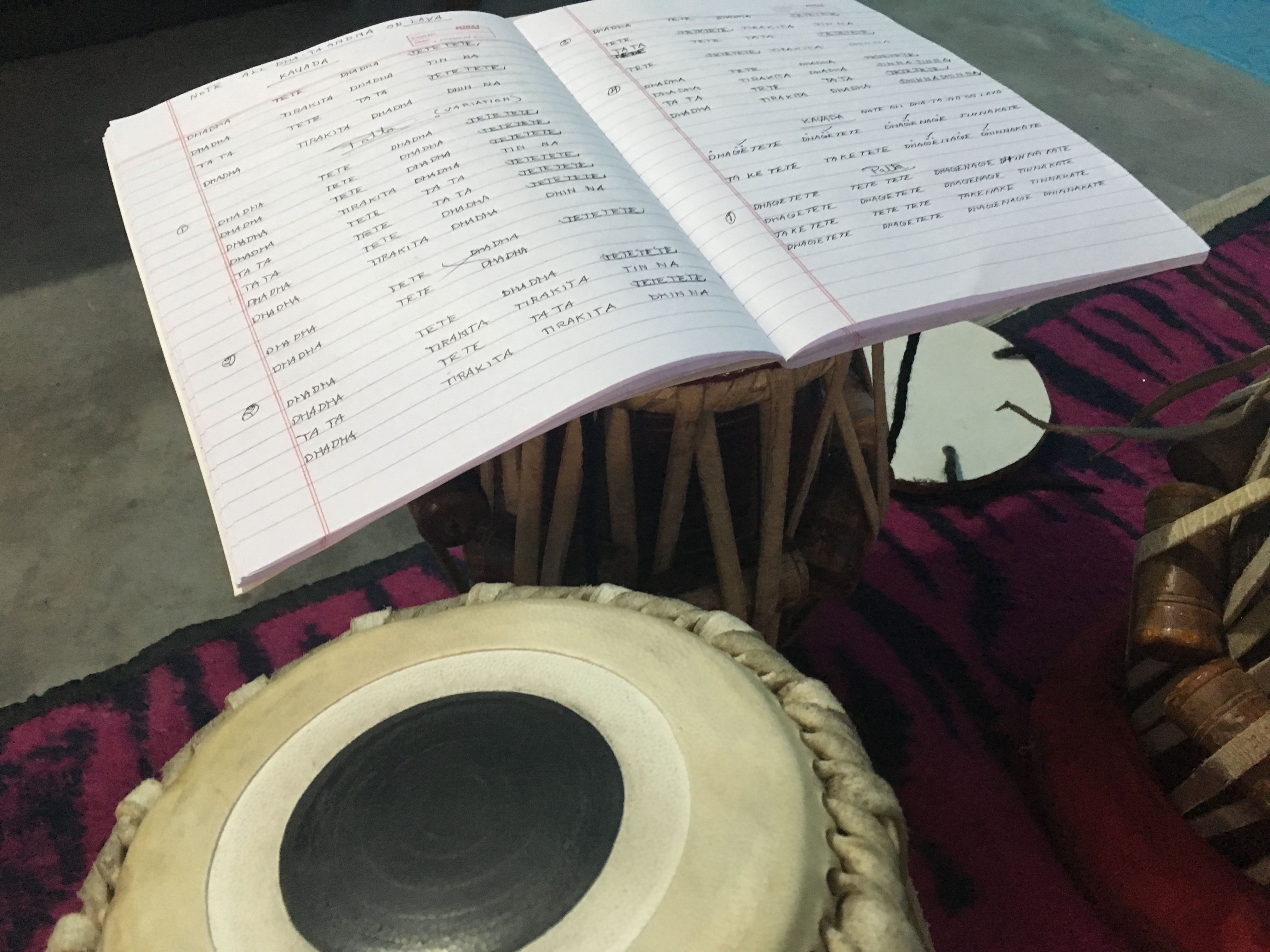

Here’s some of the coolest chops I picked up in a month of intensive tabla training in Dharamshala. (And on the left, the speed it’s supposed to be played.) #IncredibleIndia pic.twitter.com/FBEsxDFoTr

— Kris Swales (@KrisSwales) July 30, 2018