It’s 2pm, 35 degrees and somewhere just south of 100 percent humidity in Phnom Penh. The previous five hours had been spent trudging through the killing fields of the Cheung Ek Genocidal Museum, then walking the corridors of the S21 prison camp where so many Cambodians awaited their fate.

Only a brief half-time break for lunch at the Tuk Tuk Café, where a ‘Great Australian Beer Songs’ playlist inexplicably rolled through Beds Are Burning, What’s My Scene? and Khe Sanh et al, offered any respite from the horrors.

Humanity is fucked, our future is still grim, and – with the power out and the beer lukewarm when the tuk-tuk returns us to our hostel – the only way to shake it off is with a mid-afternoon run.

Zac, the genial, formerly Brisbane-based Kiwi owner of The White Rabbit hostel suggests the nearby Olympic Stadium – because why would you let never hosting an Olympic Games stop you from naming your stadium whatever you want to – as the best place to pound the pavement without dodging the endless procession of two-wheelers that constitutes Phnom Penh peak hour.

It’s a short, sweat-drenched walk west along a miracle mile of road lined with motorbike retailers (the two-wheel transport trade thrives in Phnom Penh, where every second rider is ready to turn tourist taxi at the drop of a US dollar) before the stadium appears. It’s more utilitarian coliseum than architectural wonder; 85 percent open-air cement terraces, the remainder a semi-covered grandstand, its roof echoing Cambodian pagoda design.

A stadium fit for 50,000, with none of the mod cons.

Expecting some sort of security presence, I’m surprised to find the gate open and the entire compound a hive of activity. A beach volleyball game is in full flight to my left, the ‘beach’ surface closer to dirt than sand, some combatants shirtless and smashing spikes down with brutal authority. I cross the concourse surrounding the main stadium and make my way up a long concrete ramp to the top of the terrace bowl.

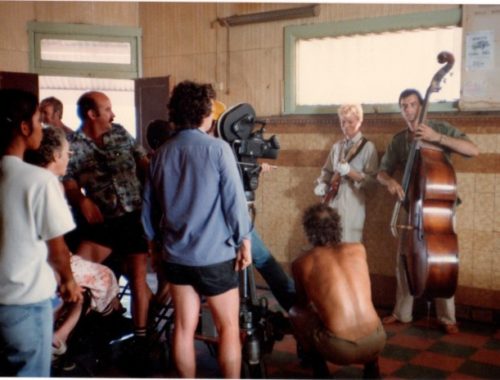

A film crew has established a unit base under a small shaded section atop the bowl. Twenty-six flagpoles, white paint flaking from them, stand naked nearby. An outdoor concert stage is mid-construction at one end of the ground, spread across the stone-covered running track and just clear of a pitch sporting football goal posts and line markings.

Cambodia Premier League footballers stretch under the shade of the main grandstand as they prepare for an afternoon training session. Cleaners tend toilet blocks tucked away in the rear of the terraces. Local school girls giggle as they pass the crazy white guy who’s about to set off along the top of the bowl.

This is oppressive heat on a grand scale, like running along the Cairns Esplanade if Cairns were five kilometres closer to the sun and bereft of sea breeze. A single 800-metre return trip from one end of the half moon of cement to the other is all it takes to realise there’s a reason no locals are treading the same path.

Commonsense prevails and I head for lower ground, taking some solace in the fact that I’m not the first Australian to struggle here. Our Socceroos hold the dubious honour of being crushed by North Korea in two 1966 World Cup Qualifiers at this very stadium, the neutral turf a result of the Asian nation’s frosty diplomatic relations with, well, pretty much everyone even then. We’re a long, long way from Stadium Australia.

At least I’m not the only amateur athlete at work on the concourse. Some local gents whose 60s must almost be over are punching ks in the opposite direction to me, dressed in long pants and sleeves like it ain’t no thing and returning my nod and smile as our laps cross paths.

A swimming pool complex behind the terraces is almost empty. The 7,000-capacity indoor volleyball court built into the broadcast side grandstand is mid-renovation. The vast cement slab behind the stand plays host to a dozen street football games. The tiny nation’s national team barely cracks FIFA’s top 200 in the world, yet more kids practice their footwork here than you’d see in a month’s worth of scratch matches in inner-city Australia.

The Olympic Stadium backdrop is symbolic; a barefoot kick around on concrete is the reality of contemporary Cambodia, a grass pitch beneath your feet is the dream. That the country has recovered from Pol Pot and his miscreants from the Khmer Rouge slaughtering a quarter of the population between 1975-79 is achievement enough; that its people are so full of hope and humour seems nothing short of a miracle. Nod and smile. “Tuk-tuk?”

Clothes completely saturated, I throw the towel in after five kilometres and buy two 600ml bottles of spring water from a nearby street vendor. The sound of tribal drums drifts out of a building at the southern end of the complex, drawing me towards it instead of the gate I entered through. A junior wrestling tournament is taking place inside – not Greco-Roman wrestling as I assume, but Khmer traditional wrestling, its local equivalent.

The two hand percussionists are seated at the corner of a 10m x 10m mat, beneath an electronic scoreboard. Their rhythms signal time for the competitors to spring into battle, their respective Red and Blue sarongs now wrapped tight around their groin area in the fashion of sumo wrestlers.

I’ve watched many sports in many parts of the world – cricket in India, football in Morocco, basketball and baseball in the USA on this trip alone – but the rules of this contest are impenetrable to the independent observer, even one versed in the nuances of such a barbaric practice as State of Origin rugby league. One hundred spectators form a perimeter around the mat, a handful more roaring their approval from a nearby grandstand. Bouts come and go quickly, the Blues seemingly from a superior dojo as they rack up a succession of easy victories.

When the biggest boys step onto the mat, the Red heavyweight quickly racks up six points in the first round, then attempts a pinning move which his opponent resists by arching his back up and somehow not breaking his neck. The lone westerner in the stands is wincing as he averts his gaze; the local spectators reach an even more fevered pitch.

As round three winds down, the Red holding a comfortable 8-4 lead, proceedings take a turn for the surreal. The opponents stop circling each other with 30 seconds left on the clock, take a step backwards, and start busting moves like B-boys at an interpretive dance workshop. The drummers up the intensity, the crowd hoots and hollers, the lone westerner cracks a broad smile.

And when the judge’s decision comes down, the bout is awarded to the Blue. Confounded by this bizarre turn of events, I gather my belongings and start the slow walk home and wonder what scoring play I’d missed.