“Modi’s about to address the nation,” said my Managing Editor, motioning to the monitor above me, or perhaps one of the many others splashing Breaking News banners across our newsroom. “He never does this. It must be pretty big.”

It was a Tuesday night like any other, except that the US electors who could be bothered to make the effort were just starting to trickle into voting booths to decide between a terrible Presidential candidate and an even worse one, and the Indian PM had decided this was the time to strike.

Never mind that the air in Delhi was so thick with smog that you could taste the sediment on your tongue if you spent more than 15 minutes in the open air; so sharp that your throat felt like it had swallowed barbed wire if you spent 25 minutes running Delhi’s streets in it; so thick that visiting British PM Theresa May had stripped hours off her life by merely spending some time breathing it in sans filtration mask.

Mmmmm, tasty.

There were bigger, more important fish to fry. Nasty fish. The type you’d need a bigger boat for.

This wasn’t readily apparent, though, as the man with the best painted-on smile this side of Peter Dutton appeared on our monitors and rattled off a lengthy list of his government’s achievements without actually saying much, as if late-era Jay-Z had prepared his speech. By the time he dropped the hook, we’d turned the volume down and got on with our work.

Separated at birth?

But then it came. To bring an end to ‘black money’ (referring to everything from counterfeit cash to corruption to untaxable cash-in-hand work) once and for all, 500 and 1000 rupee notes were being pulled from circulation as of midnight. You can deposit or trade any of the offending bills at your bank of choice until the end of 2016. 500 and 2000 rupee notes would be available in their place by Friday. A list of caveats and exceptions too lengthy to detail was explained in great length. There was no need to panic. This was not a drill.

Reactions in the newsroom ranged from “what in the actual fuck?” to “this is an act of political genius” to “what am I going to do with this 9500 rupees worth of useless money in my wallet?”, and that was just what came out of my mouth.

Election? Pfft. Modi’s ‘demonetisation’ move had just checkmated Hillary and The Donald like he was shelling chickpeas.

Text messages rolled in, first from my landlord, then one of my editors. Meme-makers got to work. I texted my girlfriend and told her to switch on the TV, then get to the nearest ATM stat. By the time I peeled myself away from my desk and to the ATM at the base of our building, it’d already been switched off. This didn’t bode well.

In summary: the Indian Prime Minister had declared somewhere in the vicinity 86% of the cash in circulation (24% of the notes by volume) illegal tender overnight, in a bid to derail the cash economy which reportedly accounted for 12% of all business done in India, without telling anyone. The big fish with their Scrooge McDuck money vaults of ill-gotten big bills either had to deposit them at the bank, thus essentially declaring the money and subjecting themselves to taxation, or burn the lot.

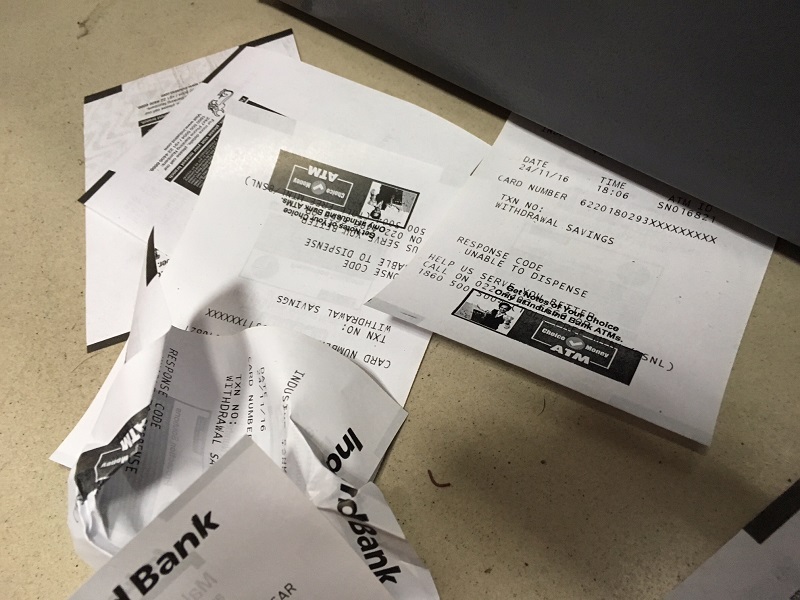

By the next morning, garbage bags full of cut-up counterfeit cash were appearing at the base of apartment towers. Now-useless notes floated in the Yamuna River. Banks were shut for 24 hours, ostensibly to take stock of their current money supply and prepare for the onslaught. And ATMs had to be reconfigured, because the shiny new notes weren’t designed to be dispensed by them.

Meanwhile, your average minnow on the street was even more fucked than the big fish.

Every bank in India since November 10.

The bank queues snaked out of every branch in Delhi from Thursday morning, and still do 15 days later. The two times I’ve made it inside a branch of my bank to withdraw cash, they haven’t had any. None of the ATMs within spitting distance of my home/work have been reconfigured.

Every time anyone is punching numbers into an ATM, a crowd anxiously gathers behind them, awaiting word from the Promised Land. Shaking your head at the people gathered expectantly behind you at the ATM has become a form of national bonding.

Sigh.

It’s inconvenient, but I’m lucky. I’ve got an apartment, a debit card, an internet connection, and a girlfriend who lives in a part of town where crisp new 2000-rupee bills spray out of ATMs like a freshly tapped oil well. (More importantly, a friend of hers who owns a petrol station gives her the good word whenever their ATM has been topped up.)

But unless she’s given me my weekly allowance, I’ve got no cash for auto drivers. None for street food, which I devour with the ferocity of a hardened local. (“Spicy?” they ask. I nod, vigourously.) None to buy vegetables from the vendors who sell fresh produce off the back of flat trays attached to pushbikes that look like they’d carbon date before Penny Farthings.

There’s always a small crowd gathered around the street vendors, so they’re somehow staying afloat, but they’re dwarfed by the queues still snaking this way and that out of banks across India; queues so long that yes, some media outlets really are keeping a death toll.

“It’s just a crisis,” the bank teller shrugged helplessly at me with the defeated look of a man who’d spent the past fortnight questioning his career choice.

“I know that, mate,” I retorted, but I had nothing else.

I gathered my disgruntled self from his desk, crossed the intersection to EFTPOS myself 200 grams of bacon at $40/kg and Lemnos haloumi at $12 a slab, strolled around the corner to rack up a $3.50 cappuccino at a nearby coffee chain, then slipped the beggar outside 20 rupees as I headed back towards my humble but well-appointed man cave.

He held the note to his forehead and said a silent prayer of thanks.

Meanwhile, at the bank…

[…] read from a local (hey Kris!) about that time the Indian PM made most of the country’s money illegal overnight, which was in […]